Note most data as of late 2021 due to embargo period.

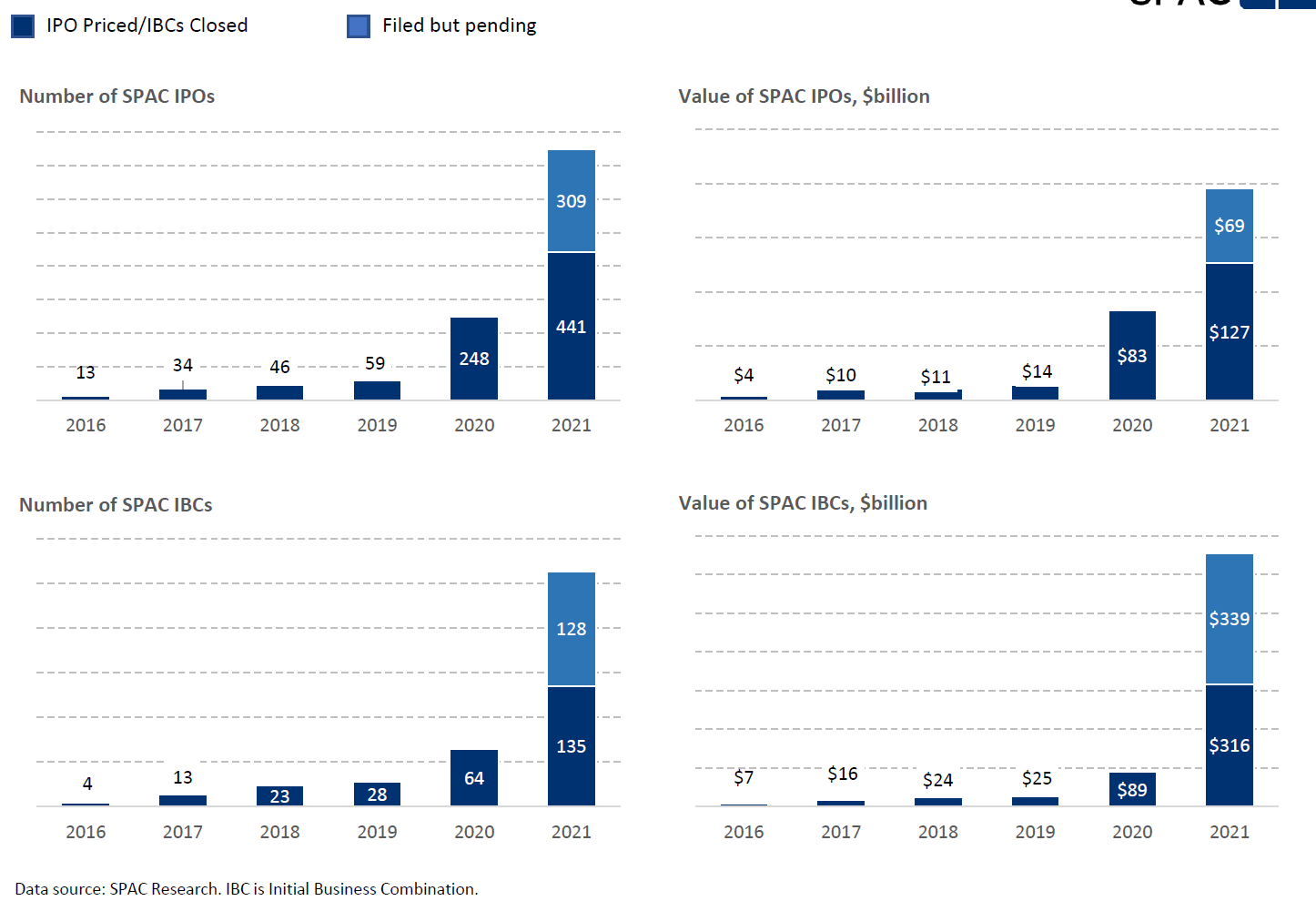

While the SPAC boom of 4Q20 and 1Q21 has not continued, there has still been a lot of activity in the space in 2021 and will be for more than a year even if another single SPAC IPO does NOT occur. While much has been made about the slowdown in the SPAC market, the SPAC IPO market is not dead yet as just last week, 6 IPOs occurred raising $1.2bn, 2 new targets were announced with an EV of over $2.1bn, and 3 transactions were closed with a combined EV of over $4bn. Please see the charts below from SPAC Research

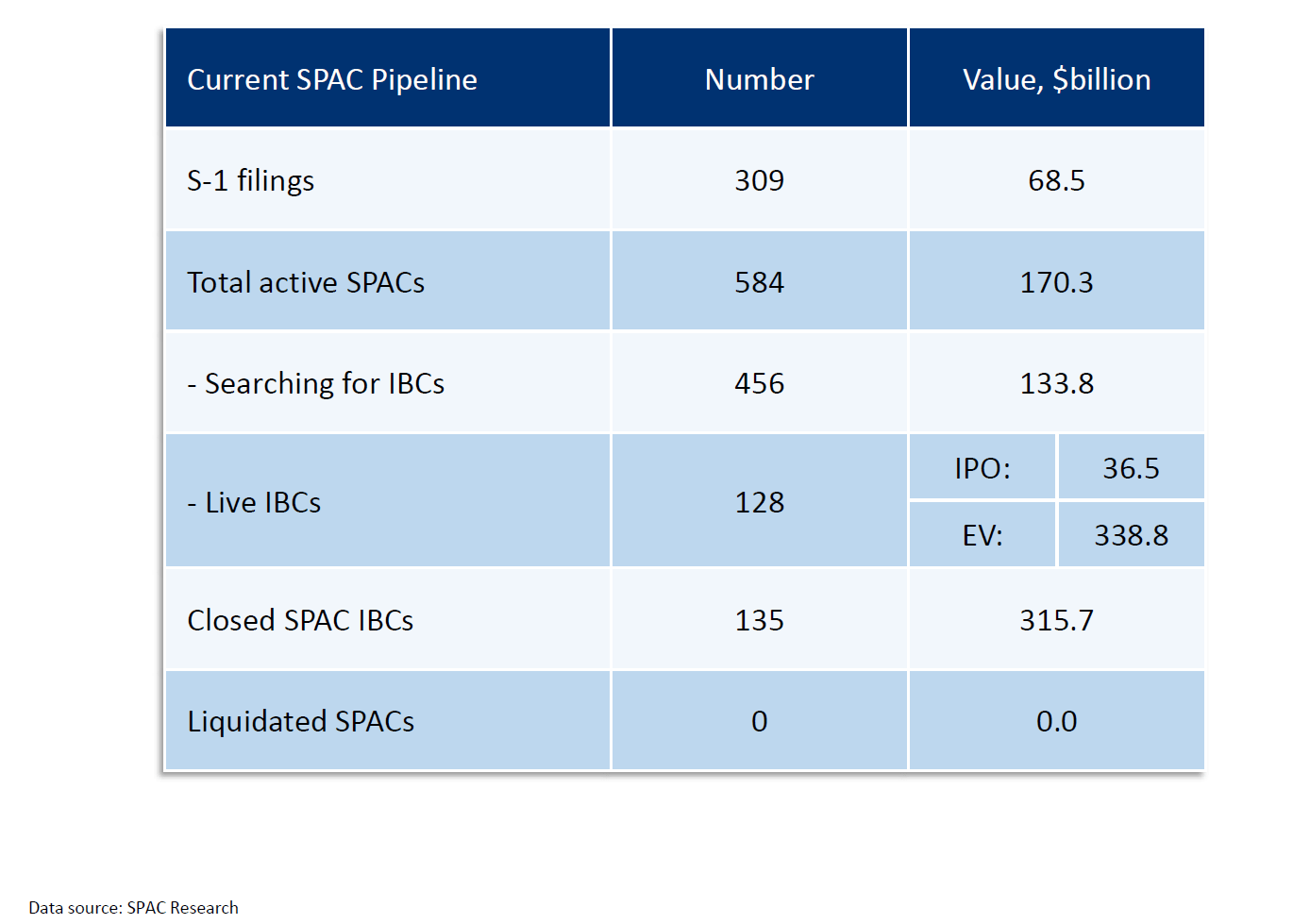

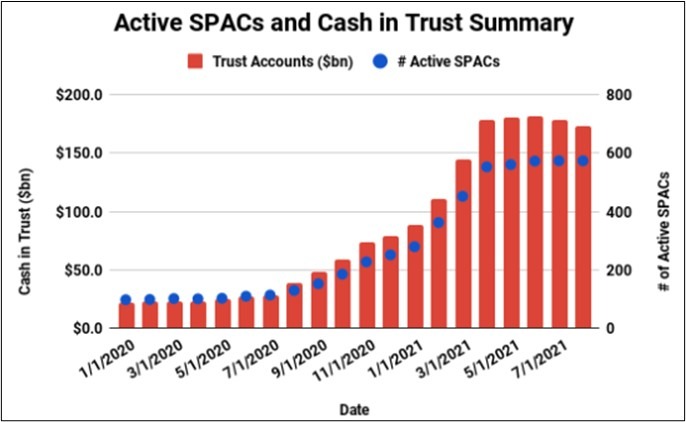

The table below shows the current SPAC pipeline. Note there are still over 450 companies shopping for a target company and over 125 SPACs that have announced a target but have yet to close the deal. This represents hundreds of billions of dollars of enterprise value. The bar chart below also shows the trend in the aggregate amount of capital in trust and active SPACs from about a month ago. SPACs are now competing more directly with private equity groups and strategic buyers for acquisition candidates. The result is probably increased valuations. This may prove to be problematic if valuations are moving higher for structures that inherently have more dilution.

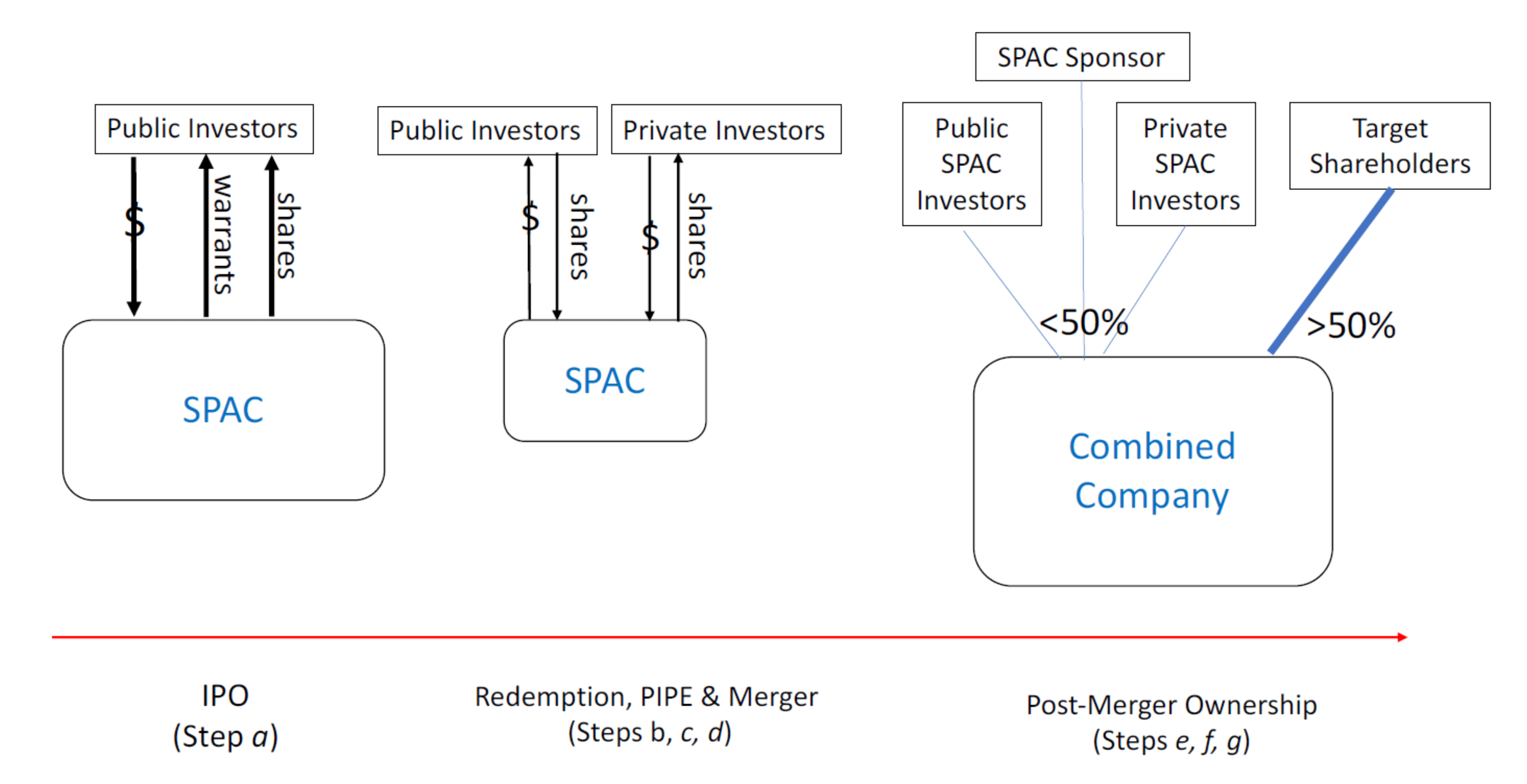

While all the data above is staggering, it may be helpful to understand the timeline or life cycle of a SPAC

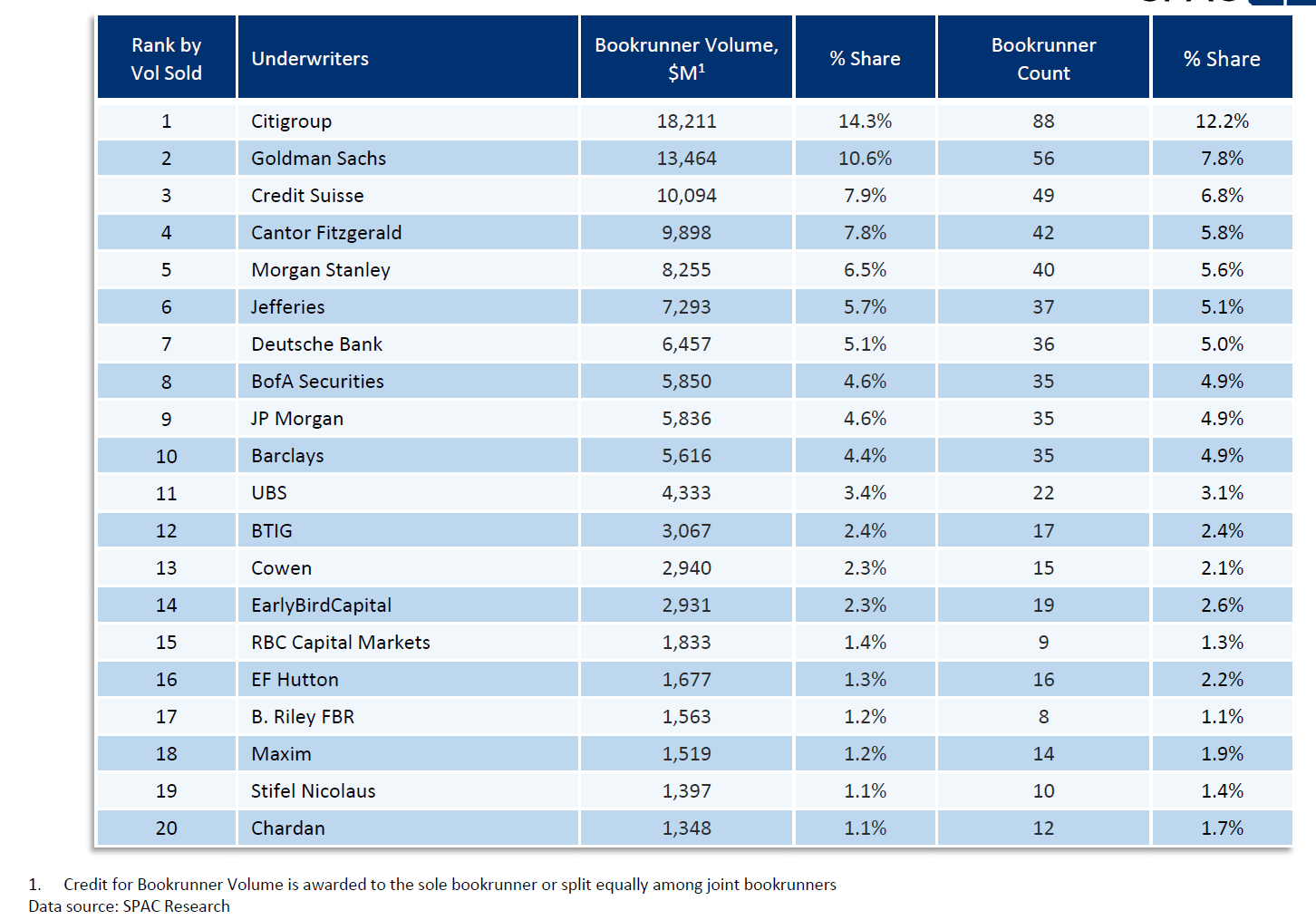

The life of a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) begins when a sponsor forms an entity, hires underwriters (see YTD Underwriter market share table below) and files an S-1 to do an initial public offering. The sponsor is someone that believes that they can raise capital for the purpose of acquiring a company. Another name for a SPAC is a “blank check” company as investors are in effect giving the sponsor a blank check with which to go find a company to buy with the capital raised. At the time the SPAC is formed, it does not have any commercial operations and could be viewed as a shell company. This enables the private company to go public without enduring the cumbersome traditional IPO process with the SEC. Additionally, while similar to a reverse merger, a SPAC shell company is “clean” in that there are not existing operations, assets and liabilities, etc., that need to be valued in a traditional reverse merger. Lots of institutional investors are IPO investors due to the arbitrage opportunities that can exist up until deal closing and the optionality that exists with the ability to redeem stock and obtain warrants (discussed later)

Sponsors typically have operational, M&A, industry, or private equity experience and are highly incentivized to close a transaction. They do not receive salaries, fees, or other forms of compensation until a transaction is consummated. In fact, they may be responsible for lawyers’ fees, D&O insurance (which has skyrocketed), and other costs. However, they typically receive a 20% equity position in the SPAC (known as the sponsor promote), excluding any warrants they receive. Consequently, as they approach the deadline to close a transaction, conflicts of interest may intensify as sponsors need to get a deal done to make money (and underwriters to collect some of their fees). Even if the sponsor is willing to pay a lot for a low-quality company, their cost basis is much lower than all the other SPAC shareholders, approaching $0, allowing the sponsor to make $ even if the SPAC or new entity trades significantly below trust value.

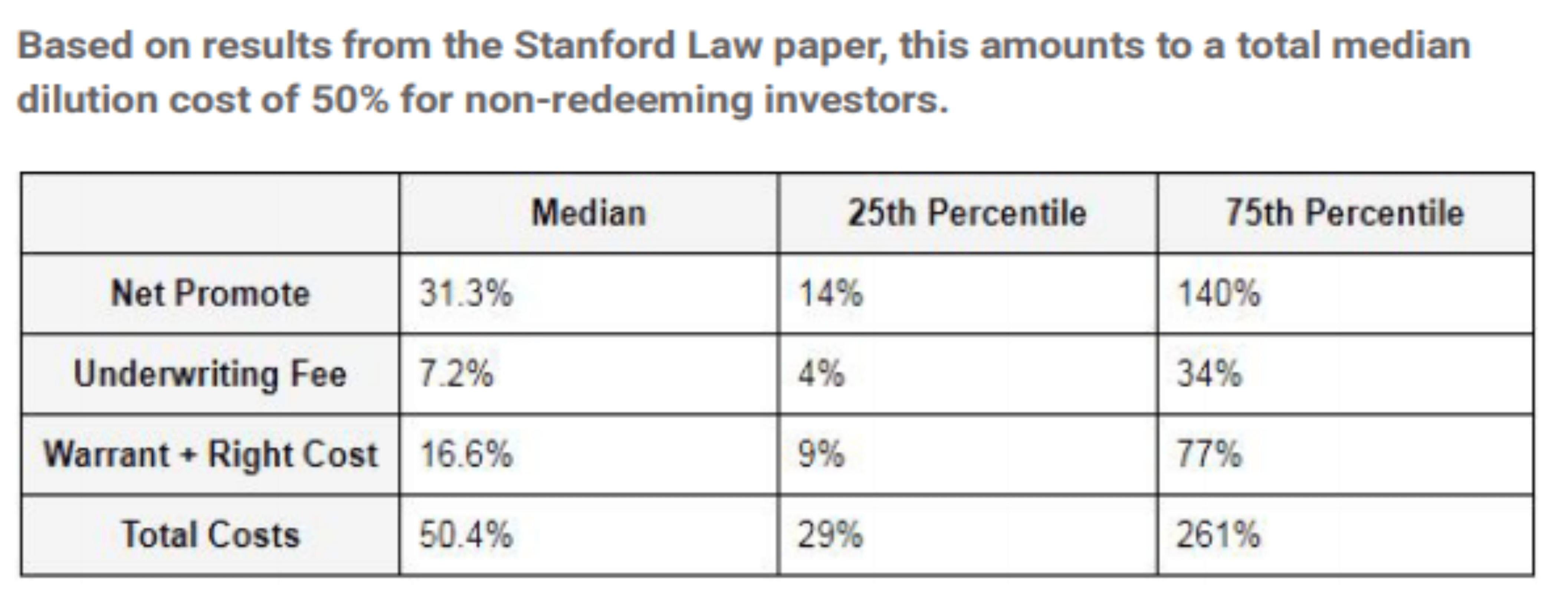

Speaking of trust value, the typical SPAC IPO price is $10. For $10, an investor receives 1 unit (see Step A above). A unit usually includes 1 share of stock and a partial or full warrant. In most cases, a SPAC with higher quality sponsors and underwriters tends to offer less warrants to entice investors than a management team that is deemed riskier or underwriters seen as lower quality. For example, a high- quality SPAC may include 1/5th of a warrant with each share of stock in a unit but a lower quality SPAC may include a full warrant with each share of stock in a unit. This affects future dilution as the lower quality SPAC would have approximately 5x as many warrants. Dilution should be a focus of all SPAC investors as the table below details how much dilution can occur due to warrants, the sponsor promote, and the underwriters.

Not long after the IPO, the unit will split and the stock and warrants will trade as separate securities. Public shareholders may trade their stock and warrants. Sponsors are usually locked up for some period of time until after the merger.

The $10/unit are put into a trust. These proceeds in the trust cannot be used for anything but cash consideration for the target company. The trust can earn interest income and so the trust/share value can actually slightly exceed the $10/share amount.

From the IPO to the time of the announcement of an acquisition target, the SPAC shares may trade from slightly below trust value (typically $10) to multiples of trust value based on liquidity, target industry, rumors about potential deals, the overall stock market, and optimism about a SPAC sponsor. If investors can find SPACs trading below trust value prior to a target announcement, this can be a good opportunity to buy shares.

The sponsor typically has 2 years to find a company to merge with/buy. When a sponsor announces a target, the stock will react based on how shareholders and the market feel about the deal. At this time the sponsors and target company will share a presentation about the merger terms and financial projections. The projections are often referred to as Safe Harbor projections. Basically, a management team can provide extremely bullish estimates with no realistic chance of achieving those goals. Some SPACs provide reasonable guidance while many others project massive growth rates and margin expansion over the next 5 years. There was even a SPAC that provided guidance 20 years into the future. Investors looking for volatility or who are confident the sponsor will announce a good deal, may want to own shares prior to the target announcement.

Often after the announcement of a target, the sponsors will seek to raise additional capital through a PIPE. PIPES can be a good way to invest in SPACs as the investors often receive additional incentives to participate in the PIPE and can often have lockups that expire before sponsor and target shareholders. Additionally, PIPE investors may get to see financials of the target before the deal is announced and before public shareholders.

The existence of a substantial pipe being raised, especially if quality investors are involved in the PIPE, can be a bullish indicator. Additionally, the size of the PIPE can change. If a SPAC set out to raise a $50mn PIPE, and it is upsized to, say $75mn, that may also be a bullish sign. Conversely, if the PIPE were downsized to less than $50mn, that could be viewed as a bearish sign. The good thing about funds raised through a PIPE is that they are much less dilutive than funds raised from the IPO as they don’t have the 20% sponsor promote. Therefore, all else being equal, an investor should prefer that more of the cash used in an acquisition of a target to be sourced from a PIPE than the SPAC IPO.

After announcement, the sponsors and the target company will try to finalize all the details and continue to update SEC filings until they have the final meeting prior to deSPAC. Prior to this date, shareholders are allowed to redeem their shares. This means that a shareholder may return a share of stock for the IPO price (usually $10), in effect, getting their money back. If the investor was an original investor in the SPAC IPO and had paid $10 for a share of stock and 1 warrant, the investor would return the share of stock, receive $10, and get to keep the warrant. If an investor purchases the stock sometime after the IPO, the investor could still return the stock for $10 but would not have the warrant. This redemption process can produce some arbitrage opportunities and also generally can put a floor in the stock price. For example, the stock is trading at $10 and the sponsor announce a target that is not well received and the stock trades down to $9. The stockholder can still redeem their stock for $10 prior to deSPAC. Given the ability to redeem for $10, the stocks usually do not trade for big discounts to trust value for very long prior to deSPAC, as investors would snatch them up and redeem for a profit. In addition, SPACs usually do not see big redemptions, if the stock is trading significant above trust value because why would an investor want to redeem a stock at $10 if it could sell it in the open market, for say $17.

If too many shareholders redeem their, this can affect the ability to complete the transaction. A minimum cash contribution exists for most deals. For example, a deal could have a minimum cash contribution requirement of $100mn. Let’s say a SPAC sold 20mn shares at $10/share and raised $200mn, but 75% of shareholders redeem. Those redemptions result in the trust only having $50mn which is only half of the minimum cash contribution. The SPAC sponsor may then have to seek a waiver or find other sources of cash to keep the deal from terminating. The sponsor may seek to raise a PIPE, sell/contribute some of the sponsor shares, issue debt, or some other form of capital raising.

*The conclusion of this article will appear in an upcoming issue of Signals. The complete white paper is available on request for a limited time, please see below.

Social Share:

Topic Tags:

Contribute Your Research

Signals

to reach a global audience of hedge funds, mutual funds, wealth managers and ETF sponsors